DIRECTING

Nathanael's work as a director has been recognized and nominated for awards across the nation. As a theatre administrator, he served as artistic director of Performance Riverside where he oversaw the artistic and fiscal operations of a nationally recognized, musical theatre company. He is an associate member of the Stage Directors and Choreographers Society (SDC). |

DIRECTOR'S NOTE

Little, if anything, is written about why Isidora Aguirre chose to adapt the 18th Century Chilean folktale – “Las Tres Pascualas” – for the stage. Her works, written largely during the mid-20th Century, were known to illuminate social inequalities and effect protest, and Las Pascualas (deemed as a feminist play by its North American curator, Expand the Canon) is hardly an exception.

Set in 1910, the play contains insinuations of the patriarchal and colonialist forces that were dominant during the time. The estate, where the play is set, is controlled by Albert, an “invalid” who is mentioned but never seen. Moreover, the three principal women in the play – known as the “Pascualas” – epitomize some of the struggles that women faced: Elvira, who married out of necessity rather than love; her mute sister, Adelaide, who does not have a voice; and her daughter, Marcela, who is undereducated, “bored,” and can only find escape through the few books available to her. All three of them yearn for freedom and choice that is exclusive only to men, and Daniel – a progressive scientist who suddenly appears at their doorstep – seems to be their means of escape.

Yet, Daniel is hardly the savior they hoped he would be. His inexplicable appearance as well as his insertion into and disruption of the family is akin to the colonialists who inserted themselves – both in culture and in blood – into the country, exploited its natural resources, and then left it in disarray. Despite the play’s tragic ending, though, I challenge you to look for a silver lining: Aguirre herself eschewed marriage, citing “It is not possible to be married and to write as I do” so perhaps what she is conveying is that salvation need not be sought from the very outside forces that oppress but rather from ourselves and our community.

Enjoy.

Set in 1910, the play contains insinuations of the patriarchal and colonialist forces that were dominant during the time. The estate, where the play is set, is controlled by Albert, an “invalid” who is mentioned but never seen. Moreover, the three principal women in the play – known as the “Pascualas” – epitomize some of the struggles that women faced: Elvira, who married out of necessity rather than love; her mute sister, Adelaide, who does not have a voice; and her daughter, Marcela, who is undereducated, “bored,” and can only find escape through the few books available to her. All three of them yearn for freedom and choice that is exclusive only to men, and Daniel – a progressive scientist who suddenly appears at their doorstep – seems to be their means of escape.

Yet, Daniel is hardly the savior they hoped he would be. His inexplicable appearance as well as his insertion into and disruption of the family is akin to the colonialists who inserted themselves – both in culture and in blood – into the country, exploited its natural resources, and then left it in disarray. Despite the play’s tragic ending, though, I challenge you to look for a silver lining: Aguirre herself eschewed marriage, citing “It is not possible to be married and to write as I do” so perhaps what she is conveying is that salvation need not be sought from the very outside forces that oppress but rather from ourselves and our community.

Enjoy.

DIRECTOR'S INTERVIEW

Why this play? Why now?

Hedda Gabler is an iconic play by the late 19th Century playwright and Father of Modern Drama, Henrik Ibsen. His plays are known for their rich, complex, and indelibly human characters. While this play has many themes, one of the most relevant is identity and the roles society expects us to play based on our perceived identity. Many of the characters are struggling with finding their freedom and being their true selves in a world that wants them to adhere to social paradigms and fit nicely in a box.

What's special about this translation/edition?

Since the play's central character is a woman and many of the issues this play tackles center around womens' role in society and their lack of freedom in a male-dominated world, I felt it was important to find a translation by a woman. I chose a version translated by Anne-Charlotte Harvey, yet adapted by Jon Robin Baitz. Of all the translations and adaptations that I read (10 of them!), Baitz's was certainly the most modern and accessible without sacrificing Ibsen's rich language, characters, and storytelling.

What should audiences expect to take away from the show?

No comment! Our plan is to simply tell the story and allow the audience to take away from it whatever they will. Ideally, the audience will walk away with diverse opinions about the characters' relationships and inner motivations.

Anything special that you would like to add to capture an audience?

Ibsen was a huge proponent of social change and was certainly an advocate for diversity, equity, inclusion, and justice. He once wrote, “The minority is always right,” and went on to say, “I mean that minority which leads the van, and pushes on to points which the majority has not yet reached.” However, Ibsen's plays are not didactic, and he doesn't try to air some problem to be put right. Rather, he strives to portray "human beings and human destinies" in all its complexities by simply – to steal from Shakespeare – holding "the mirror up to nature."

Hedda Gabler is an iconic play by the late 19th Century playwright and Father of Modern Drama, Henrik Ibsen. His plays are known for their rich, complex, and indelibly human characters. While this play has many themes, one of the most relevant is identity and the roles society expects us to play based on our perceived identity. Many of the characters are struggling with finding their freedom and being their true selves in a world that wants them to adhere to social paradigms and fit nicely in a box.

What's special about this translation/edition?

Since the play's central character is a woman and many of the issues this play tackles center around womens' role in society and their lack of freedom in a male-dominated world, I felt it was important to find a translation by a woman. I chose a version translated by Anne-Charlotte Harvey, yet adapted by Jon Robin Baitz. Of all the translations and adaptations that I read (10 of them!), Baitz's was certainly the most modern and accessible without sacrificing Ibsen's rich language, characters, and storytelling.

What should audiences expect to take away from the show?

No comment! Our plan is to simply tell the story and allow the audience to take away from it whatever they will. Ideally, the audience will walk away with diverse opinions about the characters' relationships and inner motivations.

Anything special that you would like to add to capture an audience?

Ibsen was a huge proponent of social change and was certainly an advocate for diversity, equity, inclusion, and justice. He once wrote, “The minority is always right,” and went on to say, “I mean that minority which leads the van, and pushes on to points which the majority has not yet reached.” However, Ibsen's plays are not didactic, and he doesn't try to air some problem to be put right. Rather, he strives to portray "human beings and human destinies" in all its complexities by simply – to steal from Shakespeare – holding "the mirror up to nature."

DIRECTOR'S NOTE

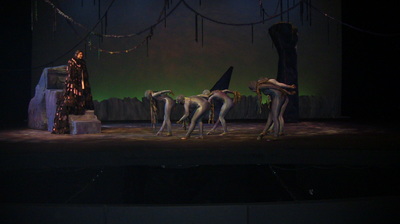

So what is “Devised Theatre”, anyway? Devised Theatre is a method of theatre-making in which the story originates from collaborative work by an ensemble.

In a typical production process, the script is chosen, the artists are hired, and then the work begins interpreting and realizing the script for the stage. In the devised process, however, there is no script at the outset. Instead, the artistic team is assembled first and then the work begins building the story from the ground-up, usually by using a “prompt” (or a piece of inspiration) from current or historical events, artwork, written work, music, or a theme or topic of interest and relevance. In this instance, I chose to follow a process developed by the Tectonic Theatre Project – one of the first theatre companies to codify a devised process and notorious for such works as The Laramie Project, 33 Variations, and I Am My Own Wife. Their process, called “Moment Work”, starts by making “unit[s] of theatrical time, building block[s] of theatrical narrative, or structural unit[s] of performance”, or simply “moments”. Through this work, there is a heavy emphasis on exploring the theatrical narrative (sound, movement, color, light, mood, sets, theatrical tension, etc.) of story making as opposed to the dramatic narrative (conflict, character, dramatic tension, plot, etc.). As most plays are crafted with a dramatic narrative, I was interested in exploring narrative that would lend itself to more abstract, nonlinear, non-text driven storytelling – where, instead of form following content, form can now inform content.

The cast, creative team, and I started our process the last week of August, first by engaging in ensemble-building exercises as well as establishing a set of “guideposts” for collaboration. We then spent the next few weeks creating moments without context or meaning. Rather, the moments were inspired by the architecture of the theatre, randomly pulled props and costumes, light sources, text, and sound. When a moment intrigued us, we would revisit it, offer varying interpretations of its meaning and narrative potential, and then document it. After we accumulated a bevy of moments, we consecutively sequenced and layered them together to see what could be further revealed. Instead of creating something that meant something, we rather sought to interpret meaning from what was created. It was inspiring work.

After we exhausted ourselves with moment making, we sat down, looked at what we had made, and then asked ourselves, “What is being revealed to us?” The dialogue that ensued led us to the theme of tonight’s performance: grief.

With the theme of grief in hand, we then gathered material on the topic, sourcing western as well as non-western perspectives. This material – which ranged from poetry to spoken word, academic articles to personal accounts, music to images – provided the prompts for yet another phase of moment making. After this phase, we then set about the arduous process of creating a story, first in a simple, outline form that was presented to the design team and then eventually fleshed out to the full script that we have today. Much of what you will see was either created by or inspired from a moment that was created at some point in the process, and all of the text that you will hear tonight is original work by the students – inspired by either music, outside sources, or the muses of their imaginations.

While thorough and deliberate, our process was somewhat truncated compared to the years that most devised companies spend creating a new work. Therefore, the piece that we present to you is certainly not done – yet it is most certainly ready – and is the result of a distillation process where only the most essential ingredients remain. To distill something down to its purest form, you need heat to convert the liquid into vapor. In our particular distillation process, that heat was the discernment, devotion, passion, and – above all else – collaborative spirit of the entire team.

Enjoy.

In a typical production process, the script is chosen, the artists are hired, and then the work begins interpreting and realizing the script for the stage. In the devised process, however, there is no script at the outset. Instead, the artistic team is assembled first and then the work begins building the story from the ground-up, usually by using a “prompt” (or a piece of inspiration) from current or historical events, artwork, written work, music, or a theme or topic of interest and relevance. In this instance, I chose to follow a process developed by the Tectonic Theatre Project – one of the first theatre companies to codify a devised process and notorious for such works as The Laramie Project, 33 Variations, and I Am My Own Wife. Their process, called “Moment Work”, starts by making “unit[s] of theatrical time, building block[s] of theatrical narrative, or structural unit[s] of performance”, or simply “moments”. Through this work, there is a heavy emphasis on exploring the theatrical narrative (sound, movement, color, light, mood, sets, theatrical tension, etc.) of story making as opposed to the dramatic narrative (conflict, character, dramatic tension, plot, etc.). As most plays are crafted with a dramatic narrative, I was interested in exploring narrative that would lend itself to more abstract, nonlinear, non-text driven storytelling – where, instead of form following content, form can now inform content.

The cast, creative team, and I started our process the last week of August, first by engaging in ensemble-building exercises as well as establishing a set of “guideposts” for collaboration. We then spent the next few weeks creating moments without context or meaning. Rather, the moments were inspired by the architecture of the theatre, randomly pulled props and costumes, light sources, text, and sound. When a moment intrigued us, we would revisit it, offer varying interpretations of its meaning and narrative potential, and then document it. After we accumulated a bevy of moments, we consecutively sequenced and layered them together to see what could be further revealed. Instead of creating something that meant something, we rather sought to interpret meaning from what was created. It was inspiring work.

After we exhausted ourselves with moment making, we sat down, looked at what we had made, and then asked ourselves, “What is being revealed to us?” The dialogue that ensued led us to the theme of tonight’s performance: grief.

With the theme of grief in hand, we then gathered material on the topic, sourcing western as well as non-western perspectives. This material – which ranged from poetry to spoken word, academic articles to personal accounts, music to images – provided the prompts for yet another phase of moment making. After this phase, we then set about the arduous process of creating a story, first in a simple, outline form that was presented to the design team and then eventually fleshed out to the full script that we have today. Much of what you will see was either created by or inspired from a moment that was created at some point in the process, and all of the text that you will hear tonight is original work by the students – inspired by either music, outside sources, or the muses of their imaginations.

While thorough and deliberate, our process was somewhat truncated compared to the years that most devised companies spend creating a new work. Therefore, the piece that we present to you is certainly not done – yet it is most certainly ready – and is the result of a distillation process where only the most essential ingredients remain. To distill something down to its purest form, you need heat to convert the liquid into vapor. In our particular distillation process, that heat was the discernment, devotion, passion, and – above all else – collaborative spirit of the entire team.

Enjoy.

DIRECTOR'S NOTE

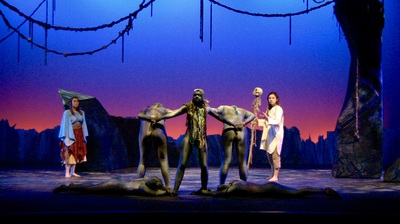

In the original Greek myth, Eurydice marries Orpheus and, shortly after her wedding, she is pursued by a covetous shepherd, steps on a serpent and suffers an untimely death. Orpheus then travels to the underworld to rescue her and – using the power of his music – softens Hades’ heart. Hades is so moved by Orpheus’ music that he grants him passage to restore Eurydice to the upperworld. Yet, in true mythological form, there is a catch. If Orpheus looks behind him to see Eurydice before she has passed through the gates, he will lose her forever. He looks and sends his lover back into the underworld for eternity.

This classic, love story has served as the inspiration for innumerable reinterpretations; our modern sensibilities seem to have as much a predilection for the “damsel-in-distress” trope and for idealizing young, romantic love as the Greek’s, yet, Sarah Ruhl – the playwright of Eurydice – rejects these tropes and provides a fresh reimagining of the original myth. In this play, Ruhl illustrates how tenuous and fickle young, romantic love can be by juxtaposing it with paternal love.

In 1994, while Ruhl was studying at Brown, her father unexpectedly passed away. To help her cope with her grief and to “have a few more conversations with him”, she wrote Eurydice and dedicated it to him. Told through the titular character’s eyes, we follow Eurydice to the underworld where – after being washed in the River Lethe – she forgets who she is. Reuniting with her father there, she gradually remembers her past, her relationship with her father, and herself. As she experiences the steadfast, unconditional love of her father, she progressively awakens to the truth, seeing with utter clarity the dubiousness of Orpheus’ love. As her father says, “There is no choice of any importance in life but the choosing of a beloved”, and in the end, Eurydice must make the ultimate choice: to choose Orpheus and lose her father, to choose her father and lose Orpheus or, to make no choice at all, and possibly lose herself.

Enjoy.

This classic, love story has served as the inspiration for innumerable reinterpretations; our modern sensibilities seem to have as much a predilection for the “damsel-in-distress” trope and for idealizing young, romantic love as the Greek’s, yet, Sarah Ruhl – the playwright of Eurydice – rejects these tropes and provides a fresh reimagining of the original myth. In this play, Ruhl illustrates how tenuous and fickle young, romantic love can be by juxtaposing it with paternal love.

In 1994, while Ruhl was studying at Brown, her father unexpectedly passed away. To help her cope with her grief and to “have a few more conversations with him”, she wrote Eurydice and dedicated it to him. Told through the titular character’s eyes, we follow Eurydice to the underworld where – after being washed in the River Lethe – she forgets who she is. Reuniting with her father there, she gradually remembers her past, her relationship with her father, and herself. As she experiences the steadfast, unconditional love of her father, she progressively awakens to the truth, seeing with utter clarity the dubiousness of Orpheus’ love. As her father says, “There is no choice of any importance in life but the choosing of a beloved”, and in the end, Eurydice must make the ultimate choice: to choose Orpheus and lose her father, to choose her father and lose Orpheus or, to make no choice at all, and possibly lose herself.

Enjoy.

DIRECTOR'S NOTE

When World War II broke out, Noël Coward put his career as a writer, composer and entertainer on hold and volunteered to serve. He ran the British propaganda office in Paris and later worked for the Secret Service, using his fame to influence America to join the Allied forces. According to Barry Day in The Letters of Noël Coward, despite his wartime work, Coward made a promise “to write the play, the film and the song that would help his fellow countrymen get through the war. Blithe Spirit was the play.”

Coward held to this promise on all three fronts: the song was a wartime anthem titled “London Pride”[1] and the film, In Which We Serve, a nationalistic piece. The titles say it all, for their aim was to instill a sense of patriotism and unity amongst the British populace. Thematically, though, Blithe Spirit seems to stand alone amid this triumvirate; there is neither reference nor even the slightest allusion to the war. Rather, Blithe Spirit served a much simpler and – dare I say – higher purpose: to provide an escape.

The play opens on a perfect summer night on the eve of a cocktail party. Dry martinis are served and had, Arcati rides her bike freely through the English countryside, and the evening’s entertainment is a séance. Nothing could be further in sentiment from the food rationing, air strikes and casualties that Coward’s fellow Englishmen were presently facing. Surely, this was Coward painting the ideal, perhaps providing a bit of an escape for himself into a life that he dearly missed. And though this is a play about ghosts of the past – both literally with the materialization of Charles’ late wife and metaphorically with the unveiling of past marital affairs – the play handles these rather heavy topics with a very light hand; Coward gives his audience permission to have a much needed laugh.

This is a play about the supernatural and marital discord, but more specifically, how relationships of the past can haunt us in the present. The title of the play was taken from the first line of Percy Bysshe Shelley’s poem, “To a Skylark”: "Hail to thee, blithe Spirit! / Bird thou never wert." In the poem, the skylark is depicted as something ethereal and unseen, yet its song of joy is always heard. Although the title of the play points directly to its supernatural theme, it also symbolizes those things in our lives that cannot be seen yet can most assuredly be felt: faith is one and love, another. Ruth and Elvira seem to have no faith in Charles, yet they are eaten away by a jealous love for him, and it is this dichotomy that is the driving force in the play. “Love is a strong psychic force,” Madame Arcati says, “It can work untold miracles.” And, in Blithe Spirit, Coward humorously depicts the miracles (and disasters) that love can work, particularly when it is rife with jealousy and devoid of faith.

Enjoy.

[1] In 1955, Mary Martin (a native of Texas) and Coward performed on a CBS television special called “Together With Music”. Martin sang “London Pride” for Coward and Coward followed up by singing “Deep in the Heart of Texas” for her, subsequently bringing the house down. Daggum right he did!

Coward held to this promise on all three fronts: the song was a wartime anthem titled “London Pride”[1] and the film, In Which We Serve, a nationalistic piece. The titles say it all, for their aim was to instill a sense of patriotism and unity amongst the British populace. Thematically, though, Blithe Spirit seems to stand alone amid this triumvirate; there is neither reference nor even the slightest allusion to the war. Rather, Blithe Spirit served a much simpler and – dare I say – higher purpose: to provide an escape.

The play opens on a perfect summer night on the eve of a cocktail party. Dry martinis are served and had, Arcati rides her bike freely through the English countryside, and the evening’s entertainment is a séance. Nothing could be further in sentiment from the food rationing, air strikes and casualties that Coward’s fellow Englishmen were presently facing. Surely, this was Coward painting the ideal, perhaps providing a bit of an escape for himself into a life that he dearly missed. And though this is a play about ghosts of the past – both literally with the materialization of Charles’ late wife and metaphorically with the unveiling of past marital affairs – the play handles these rather heavy topics with a very light hand; Coward gives his audience permission to have a much needed laugh.

This is a play about the supernatural and marital discord, but more specifically, how relationships of the past can haunt us in the present. The title of the play was taken from the first line of Percy Bysshe Shelley’s poem, “To a Skylark”: "Hail to thee, blithe Spirit! / Bird thou never wert." In the poem, the skylark is depicted as something ethereal and unseen, yet its song of joy is always heard. Although the title of the play points directly to its supernatural theme, it also symbolizes those things in our lives that cannot be seen yet can most assuredly be felt: faith is one and love, another. Ruth and Elvira seem to have no faith in Charles, yet they are eaten away by a jealous love for him, and it is this dichotomy that is the driving force in the play. “Love is a strong psychic force,” Madame Arcati says, “It can work untold miracles.” And, in Blithe Spirit, Coward humorously depicts the miracles (and disasters) that love can work, particularly when it is rife with jealousy and devoid of faith.

Enjoy.

[1] In 1955, Mary Martin (a native of Texas) and Coward performed on a CBS television special called “Together With Music”. Martin sang “London Pride” for Coward and Coward followed up by singing “Deep in the Heart of Texas” for her, subsequently bringing the house down. Daggum right he did!

DIRECTOR'S NOTE

Written around 1598, Much Ado About Nothing is by far one of Shakespeare’s most deftly written plays in terms of dialogue and plot structure. A social comedy, Shakespeare adroitly uses deception and machination in order to instigate, invert and sabotage courtship and love. Joss Whedon’s most recent film revival of the play is a testament to its popularity and accessibility.

So the questions one must ask are: why remount a play that was written over 400 years ago now, and are its themes still socially relevant? Also, are there any elements of the play that may estrange a contemporary, American audience? There are two predominant circumstances that were potentially distancing and inspired our concept: Leonato’s condemnation of his daughter and Don John’s ostracism for being a bastard. What sort of present day society denounces a woman for having premarital sex and likewise shuns a man for being born into something that he has no control over? My research inevitably drifted towards religious fundamentalism.

Moreover, the misogynistic elements in the play were hard to ignore. There is little to no mention of the man whom Hero (supposedly) had an affair with until his later capture and examination; the fault is placed principally on her. Likewise, as Leonato remarks of Claudio and Don Pedro (the men who disgraced her): “If they speak but truth of her / These hands shall tear her. If they wrong her honour / The proudest of them shall well hear of it.” Paraphrased, if Hero is found to be unchaste, she will be beaten, possibly killed; however, if the men were found to have falsely accused her, they shall merely be ... scolded? Not quite a measure for measure, is it?

Shakespeare, though, is not a misogynist. His strongest and most iconic character in Much Ado – Beatrice – lends a much needed voice which outrightly criticizes this male dominated world and lambasts the men who govern it. One of her most famous lines is uttered moments after Hero’s shaming: “O God that I were a man! I would eat his heart in the marketplace!” If she were a man, she may revenge her cousin and attain a kind of poetic justice. Yet as a woman in this world, she cannot.

So does this play still hold social relevancy? Do we still live in a male dominated world? Yes and yes. From the disparities that still exist in the workplace to the sexual objectification still prevalent in media and advertising points to an undeniable and heavy-handed male presence in the inner-workings. Hopefully, we may eventually arrive at the same conclusion that Shakespeare does at the end of the play: “Man is a giddy thing.” Giddy – in this context – meaning unstable and apt toward change.

Enjoy.

So the questions one must ask are: why remount a play that was written over 400 years ago now, and are its themes still socially relevant? Also, are there any elements of the play that may estrange a contemporary, American audience? There are two predominant circumstances that were potentially distancing and inspired our concept: Leonato’s condemnation of his daughter and Don John’s ostracism for being a bastard. What sort of present day society denounces a woman for having premarital sex and likewise shuns a man for being born into something that he has no control over? My research inevitably drifted towards religious fundamentalism.

Moreover, the misogynistic elements in the play were hard to ignore. There is little to no mention of the man whom Hero (supposedly) had an affair with until his later capture and examination; the fault is placed principally on her. Likewise, as Leonato remarks of Claudio and Don Pedro (the men who disgraced her): “If they speak but truth of her / These hands shall tear her. If they wrong her honour / The proudest of them shall well hear of it.” Paraphrased, if Hero is found to be unchaste, she will be beaten, possibly killed; however, if the men were found to have falsely accused her, they shall merely be ... scolded? Not quite a measure for measure, is it?

Shakespeare, though, is not a misogynist. His strongest and most iconic character in Much Ado – Beatrice – lends a much needed voice which outrightly criticizes this male dominated world and lambasts the men who govern it. One of her most famous lines is uttered moments after Hero’s shaming: “O God that I were a man! I would eat his heart in the marketplace!” If she were a man, she may revenge her cousin and attain a kind of poetic justice. Yet as a woman in this world, she cannot.

So does this play still hold social relevancy? Do we still live in a male dominated world? Yes and yes. From the disparities that still exist in the workplace to the sexual objectification still prevalent in media and advertising points to an undeniable and heavy-handed male presence in the inner-workings. Hopefully, we may eventually arrive at the same conclusion that Shakespeare does at the end of the play: “Man is a giddy thing.” Giddy – in this context – meaning unstable and apt toward change.

Enjoy.

DIRECTOR'S NOTE

You and me. That is how it starts. The two factors in an equation which resolves out into either heaven or hell, and most likely both. If there is a human predicament, this is it. –Athol Fugard

This phrase, written by Fugard in an introduction to the play, seems to capture its ethos. Tackling an issue as broad as Apartheid is an ambitious undertaking, yet Fugard chooses to examine it under a microscope between a “you” and a “me”: brothers. One white-skinned, the other black. One with all the advantages of a privileged upbringing, the other with all the hardship of a disadvantaged one.

Written at the beginning of his career, Blood Knot marks what Fugard characterizes as the play where he found his voice. It debuted in Johannesburg, South Africa in 1961, receiving only one performance yet delineating a milestone in the timeline of theatre history. It was the first time ever in South Africa when a black man and a white man appeared on stage together.

Let’s take a step back and examine what this really meant. When this play opened to the public, South Africa was entrenched in the mire of Apartheid, afflicting the people of South Africa on a much deeper level than its agency. Along with the dictated segregation, discrimination and racial labeling inherent in Apartheid policy, South African’s had to stand by and watch their way-of-life, their land and their very lives be ripped out from under them. They were treated like animals, made to work as slaves and live in “townships” (a euphemism for squalor). This wasn’t merely segregation and oppression. This was outright cruelty or, as Morris says, “Inhumanity!” Indeed, this play’s debut was a true milestone.

Research reveals that the title Blood Knot is not just a metaphor. In literal terms, it’s a fisherman’s knot used to join two lines of similar (and equal) size. A principal characteristic of the blood knot is the more tension that’s applied to the line, the tighter and stronger it becomes. Nothing could more aptly characterize the journey of Morris and Zach’s relationship. Their racial difference, disparate upbringings and subsequent estrangement has caused the knot between them to become tenuous. Their only remedy, as they discover, is to employ all the tension necessary – no matter how unbearable – so that they may wring out the shame, guilt and turmoil that exists within them.

At its very heart, this is a story about brotherhood. Throughout the play, they periodically remind each other of this fact as if to affirm who they really are: a “you” and a “me.” Nothing more. As Fugard notes, “that is how it starts.” I would add that that is also how it ends.

Enjoy.

This phrase, written by Fugard in an introduction to the play, seems to capture its ethos. Tackling an issue as broad as Apartheid is an ambitious undertaking, yet Fugard chooses to examine it under a microscope between a “you” and a “me”: brothers. One white-skinned, the other black. One with all the advantages of a privileged upbringing, the other with all the hardship of a disadvantaged one.

Written at the beginning of his career, Blood Knot marks what Fugard characterizes as the play where he found his voice. It debuted in Johannesburg, South Africa in 1961, receiving only one performance yet delineating a milestone in the timeline of theatre history. It was the first time ever in South Africa when a black man and a white man appeared on stage together.

Let’s take a step back and examine what this really meant. When this play opened to the public, South Africa was entrenched in the mire of Apartheid, afflicting the people of South Africa on a much deeper level than its agency. Along with the dictated segregation, discrimination and racial labeling inherent in Apartheid policy, South African’s had to stand by and watch their way-of-life, their land and their very lives be ripped out from under them. They were treated like animals, made to work as slaves and live in “townships” (a euphemism for squalor). This wasn’t merely segregation and oppression. This was outright cruelty or, as Morris says, “Inhumanity!” Indeed, this play’s debut was a true milestone.

Research reveals that the title Blood Knot is not just a metaphor. In literal terms, it’s a fisherman’s knot used to join two lines of similar (and equal) size. A principal characteristic of the blood knot is the more tension that’s applied to the line, the tighter and stronger it becomes. Nothing could more aptly characterize the journey of Morris and Zach’s relationship. Their racial difference, disparate upbringings and subsequent estrangement has caused the knot between them to become tenuous. Their only remedy, as they discover, is to employ all the tension necessary – no matter how unbearable – so that they may wring out the shame, guilt and turmoil that exists within them.

At its very heart, this is a story about brotherhood. Throughout the play, they periodically remind each other of this fact as if to affirm who they really are: a “you” and a “me.” Nothing more. As Fugard notes, “that is how it starts.” I would add that that is also how it ends.

Enjoy.

DIRECTOR'S NOTE

Nearly three years ago, I awoke one morning and realized that the life I was living was not the life that I wanted. I came to Los Angeles to pursue an acting career yet somehow, over the course of six years, I had unwittingly been swept up in the corporate world, on the fast track towards a career in finance. I wore a fine suit, traveled the country and stayed in swanky hotels. I sweated over the bottom line, adopted the company’s core values as my own and contributed religiously to my 401(k). It was a good life but not ‘the life.’ I was sitting like a duck, in a state of unrest and waiting for some outside force to save me or – to quote the last verse of the Cuckoo’s Nest nursery rhyme – a “goose to swoop down and pluck [me] out.” It was then I realized that nothing would save me; I needed to save myself.

The mental patients in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest are swept up in their own ‘corporate world’; however, their world is much darker – for it contains a parasite which is embedded deep within their psyches. A parasite that has stealthily taken root, slowly infecting them until, as Chief Bromden says, “they got no innards, just some beat-up gears and stuff, and all they bleed is rust.” They’re so infected that their only chance of salvation is for some outside force to swoop down and save them.

McMurphy – the play’s protagonist – does just that. He shines a light on the truth, ultimately reviving the men from their catatonia. (In fact, his brief presence alone does more for them therapeutically than all the time they’ve spent in the hospital.) They have all become subjugated by what Chief Bromden refers to as “The Machine,” indoctrinated by the “Therapeutic Community” and by threats of electroshock therapy and lobotomies. The presence of the chronic patients (the half-dead, walking vegetables), serve as a dark and constant reminder of what happens to someone when they dissent. These men desperately need a savior. Or better yet, a martyr.

There are myriad interpretations as to the meaning of the title: One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. The one I like the most? The “nest” is a sheltered, little world of sticks and grass that we cannot see beyond. Yet, if we’re the least bit aware and happen to look up at the right moment, we may just see something fly overhead when we never knew that flight was even possible. And maybe our myopic view will widen just enough to catch a glimpse of the vast, colorful world that exists outside. You and I both know that there’s more out there that we don’t yet quite see or have the capacity to comprehend, yet we can hope that a McMurphy will someday come along and perhaps shed some light.

Enjoy.

The mental patients in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest are swept up in their own ‘corporate world’; however, their world is much darker – for it contains a parasite which is embedded deep within their psyches. A parasite that has stealthily taken root, slowly infecting them until, as Chief Bromden says, “they got no innards, just some beat-up gears and stuff, and all they bleed is rust.” They’re so infected that their only chance of salvation is for some outside force to swoop down and save them.

McMurphy – the play’s protagonist – does just that. He shines a light on the truth, ultimately reviving the men from their catatonia. (In fact, his brief presence alone does more for them therapeutically than all the time they’ve spent in the hospital.) They have all become subjugated by what Chief Bromden refers to as “The Machine,” indoctrinated by the “Therapeutic Community” and by threats of electroshock therapy and lobotomies. The presence of the chronic patients (the half-dead, walking vegetables), serve as a dark and constant reminder of what happens to someone when they dissent. These men desperately need a savior. Or better yet, a martyr.

There are myriad interpretations as to the meaning of the title: One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. The one I like the most? The “nest” is a sheltered, little world of sticks and grass that we cannot see beyond. Yet, if we’re the least bit aware and happen to look up at the right moment, we may just see something fly overhead when we never knew that flight was even possible. And maybe our myopic view will widen just enough to catch a glimpse of the vast, colorful world that exists outside. You and I both know that there’s more out there that we don’t yet quite see or have the capacity to comprehend, yet we can hope that a McMurphy will someday come along and perhaps shed some light.

Enjoy.